NFTs Incorporate Monetization for Online Creators, Branding Drives Demand and Value

Credit goes to Hadi Alaouieh and Jiwoo Jeong for inspiring and co-authoring this piece. Thanks to Hanna Halaburda for providing comments and feedback.

Introduction

Background and the different NFT standards

Introduced in late 2017, NFTs are still under development and have undefinable growth. Although the technology behind this recent implementation of blockchain-based tokens is nascent, it can be assessed in great depth. This paper explores the foundations of NFTs to determine how they can incorporate monetization for online creators in the digital sphere and the role branding plays in promoting this.

Blockchains and smart contracts are secured through a consensus protocol. Ethereum is the first blockchain protocol that supports virtual machines for Turing complete script languages; it’s public, permissionless, and runs smart contracts on its software.1 The ERC-20 are community agreed standards for the creation of fungible tokens on Ethereum, serving as a right to the protocol. However, the ERC-20 standard is limited to fungible tokens, so ERC-721 was created to allow for non-fungibility. Essentially, NFTs built on the ERC-721 standard are indivisible and provably unique. Therefore, they can represent ownership of digital and virtual assets.2

ERC-1155 is a new standard which brings the idea of semi-fungibility. With this standard, IDs represent not single assets but classes of assets. For example, an ID might represent “arrows” in a video game. If a wallet were to own 500 of these arrows, the balanceOf function would return the total number of arrows owned by the wallet. Transfer would also be largely facilitated since the wallet owner could transfer as many arrows as they’d like to at once, by calling the transferFrom function with the “arrow” ID. This makes it much more efficient than the ERC-721 standard (where a user would have to call the transferFrom 500 times to transfer 500 arrows) as the user would only have to call the transferFrom function once with quantity 500 to transfer all 500 arrows. However, this increased efficiency comes with a cost. There is loss of information as we can no longer trace the history of an individual arrow.

It is important to note that an ERC-721 asset could also be built using the ERC-1155 standard. The difference would be that you’d have a unique ID and a quantity of 1 for each asset. This standard gives NFT creators more flexibility, which is why it has been growing in popularity.3

The ERC-998 standard allows for composability – this means that an NFT can own non-fungible assets, fungible assets, or both. While it has not seen popular adoption yet, there could be incredibly interesting use cases for this standard.

Properties of NFTs on the blockchain4

Standardization: unlike traditional digital assets, which have no unified representation in the digital world, NFT developers can build common standards related to transfer, ownership, and access control by representing them on public blockchains. These are similar to the building blocks of the internet, such as using PNG and JPEG formats for images or HTML/CSS for displaying web content.

Interoperability: NFTs move between wallets, marketplaces, and virtual reality, thanks to open standards providing a reliable and permissioned API.

Tradability: traded freely in open marketplaces, users can take advantage of diverse trading formats such as bundling, auctions, bidding, and they can do so in any currency.

Liquidity: the fact that NFT-enabled unique digital assets are easily tradable means that they are highly liquid. They will have a market with demand regardless of intrinsic value.

Immutability and provable scarcity: developers use smart contracts to control the supply of NFTs and to maintain their properties over time.

Programmability: there is no limit to creativity since NFTs are fully programmable.

Ownership

How are NFTs related to ownership?

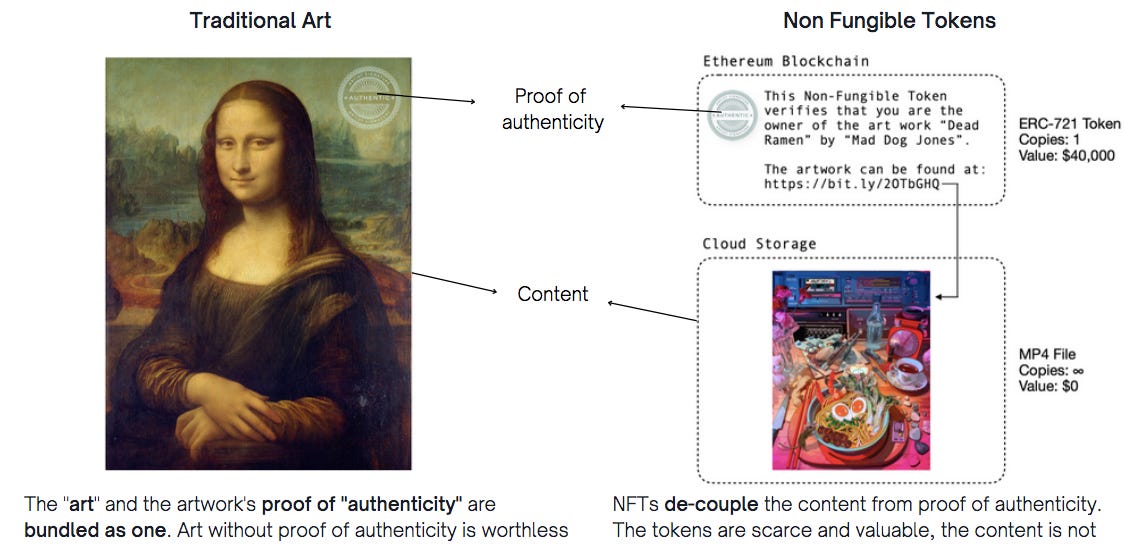

An NFT is a digital non-fungible token which is linked cryptographically to the digital asset. This is like how books live on shelves in a library – they aren’t directly attached to their library cards. This means that a copy of the digital asset stays off-chain and the only thing that is recorded on the blockchain is the digital hash (tokenID) associated with the token, which acts as a digital certificate of authenticity. Therefore, when a user buys an NFT, they are purchasing the token itself, which is not the same as purchasing the digital asset that is linked to the token since the token itself does not result in the transfer of any rights or obligations as to the asset.5 Below is an example that compares traditional art to NFT art.

Purchasing the token may still involve other rights such as the transfer of possession of a digital asset, as a matter of contract, but this is entirely dependent on the terms of sale. For example, purchasing an NBA Top Shot collectible gives the owner the limited license to use, copy, and display the images/videos associated with the particular NFT only for non-commercial, personal use. Beeple’s NFT, which sold at Christie’s auction, included some display rights in the image, but Beeple retained copyright and presumably a copy of the digital image as well.6

Storage

NFTs include a URL that will take you to the digital asset they represent. This poses problems for NFTs as the owner of the domain will have to make sure it is maintained correctly so that the NFT does not disappear. As the buyer, this is something you have no control over, unless you buy out the entire domain and pay to keep it running online.

To solve this, many NFTs use a system called IPFS, or InterPlanetary File System: a protocol and peer-to-peer network for storing and sharing data in a distributed file system. Rather than identifying a specific file at a specific domain, IPFS addresses let you find a piece of content so long as someone somewhere on the IPFS network is hosting it. This system gives buyers more control as they can pay to keep their NFT’s files online.

Another option would be to use Arweave to store the content, as it allows creators to make a one-time payment for file storage. The file will be stored for as long as the Arweave network persists.7

Monetization

How do differences in issuance affect monetization?

Perhaps the most exciting promise of NFTs is the support for royalties paid to creators as they allow the original creator of an NFT to make a percentage of any subsequent sales of their work. This creates a world of possibilities for creators to use a wider range of inputs in their products and completely redefine what being a creator means.8

On the other hand, all of the sale terms are not coded into the token. Just because a user buys an NFT it doesn’t mean that that user will be deemed later to have been bound by the terms of sale that were initially associated with it. It could also depend on what the user agreed upon when making the purchase.

Therefore, most NFT platforms provide a license agreement which includes the sale terms to make sure that the agreement between the original seller and first purchaser is based on symmetric information. This is because royalties aren’t natively supported on the Ethereum blockchain yet, so royalty systems are provided by the marketplaces which run on Ethereum. Each marketplace has its own rules and sales terms so, if an NFT is then traded in a secondary market, all subsequent sales are beyond the seller’s control.

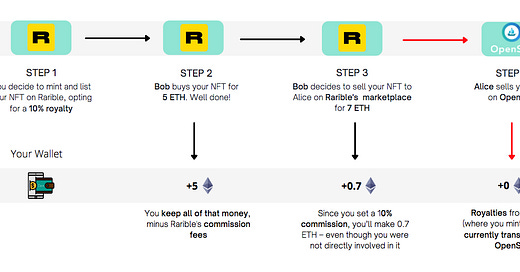

For example, if someone mints and sells their NFT on Rarible and selects a 10% royalty, each time their NFT is sold on Rarible they will retain 10% of the sale (minus commission fees). But if the new owner decides to sell the same NFT on OpenSea, the creator won’t get any royalties because the royalties from Rarible are not currently transferable to OpenSea.9

Problems with secondary market trading and royalties arise from the fact that ERC-721 marketplaces are not standardized, and implementation of standards is voluntary. Royalty systems are embedded within the marketplaces instead of the tokens, hence, secondary sales in non-compatible markets with the primary market will exclude the initial creator from the intended royalties. Currently, there is no way to ensure standardization across the markets (although there is an interesting proposal in the works). The exclusive and unique royalty systems are intended to bind the creators and traders to the primary market, which increases the commission revenue for the marketplace.10

Branding

How does branding justify a higher price for NFTs?

As discussed, owning an NFT does not mean you own the content behind it, and it has been hard to monetize NFTs across marketplaces too, but some have still sold for an incredible amount of money.

While the price is determined by supply and demand, each NFT that is branded by an established organization ensures credibility or authenticity from the chartered brand. For example, Beeple’s “FIRST 5000 DAYS” recently sold for $69 million because it was sold at Christie’s, a centuries-old auction house. NBA Top Shots allowed the NBA to raise $357 million because they were backed by the NBA brand.11

This credibility or authenticity ensured by a brand is extremely valuable because, if you are the buyer of an NFT, you have to trust that the creator won’t issue other NFTs for a specific digital file, enforcing the scarcity of that NFT. In turn, this makes the NFT legitimate. And, since the reputation of the chartered brand is on the line when they issue or endorse an NFT, as a buyer you are more likely to trust them and trust that your NFT will retain value over time.

Moreover, branding by established organizations enables an NFT to be shared and seen online more than others, accruing more cultural value over time. For example, there was mass production of Warhol’s imagery, whether in the form of posters, clothing, digital imagery. This increased the notoriety of his imagery, which makes owning the original work more thrilling, also due to the social status that comes with it. If this notoriety increases after purchase, the value from reselling the work can increase. Hence, NFTs allow collectors to have similar benefits to owning a physical work of art, as well as the benefits associated with having their collection gain notoriety by being freely shared across the internet.12

Social Tokens: Branded NFTs with Distinction

What are social tokens and how can they be useful for creators?

Social tokens are tokens backed by the reputation of an individual, brand, or community. These can be in the form of NFTs as well as fungible tokens and they are built around the premise that a certain community will increase in value over time, so they are a great means for users to share financial upside with their favorite creators. Furthermore, social tokens can also be used by influencers to reward their most loyal supporters by offering tokenized programmable access, which may include various perks and exclusive content based on their contributions.13

For example, Mirror.xyz released the $WRITE token which is the crypto alternative to the traditional invitation system. By burning one $WRITE token, users are given the power to publish one post on the platform (tokenized programmable access), which includes a unique name on ENS (*.mirror.xyz) and a minted publication. Owning the $WRITE token also gives users the power to vote on the direction and governance of the protocol. Another example is a discord bot called Collab.Land which lets communities create their own token-gated (ERC-721 or ERC-20) discords, forcing members to have “skin in the game”.14

Independent NFT creators in the future will have the ability to realize the full upside of their NFT creations and earn their built-in royalties. They will want to pursue this model if they want to acquire all the rights associated with the media and display “ownership”. However, NFT creators pursuing a collective model by fractionalizing the royalties of an NFT (which can be represented as fungible tokens) will gain greater distribution because fractional owners have an incentive to help them sell the NFT at a higher price. Instead of creating social tokens around a community, they could be created to represent the royalties of a digital object, aligning members on the desired outcome – the success of the NFT – with a finite time horizon (when the NFT sale occurs). The buyers of fractional tokens would do so to speculate on the value of the asset in the future or to contribute to the success of the sale as, when the sale occurs, they would receive the royalties in proportion to the number of tokens that they own.15

In Conclusion

Overall, the demand for and the value of an NFT is driven by the thrill of owning it and showing it off, coupled with the ability to sell and monetize it in the future. Branding plays an extremely important role in driving the value of NFTs as the credibility and authenticity of a brand gives the token legitimacy. By putting their reputation on the line, brands ensure that, for example, there will not be multiple NFTs issued that are linked to the same digital file. Furthermore, even if this was to happen, the first NFT that was issued is likely to be the one that will retain value over time since you’d be able to tell which one was issued first, which one is the legitimate NFT. This example can also be used to explain why, for instance, Tim Berners-Lee minting and selling an NFT of the original source code for the World Wide Web (which he wrote) is legitimate, whereas we would have a much harder time doing the same.

Hence, the value of an NFT and the possibility of monetizing it in the future is all about legitimacy. If everyone can agree that a given NFT is cool (or it was issued by a legitimate entity), compared to another NFT which people deem to be boring (or it was issued by an illegitimate entity), then people are much more likely to demand the cool NFT as the thrill of owning it and showing it off is the greatest. This also means that the owner will be able to resell it for a higher price because of this consensus that arises around the NFT.

Legitimacy can be used to explain most social status games, such as property rights, language, and blockchain consensus, which works the same way:

The only difference between a soft fork that gets accepted by the community and a 51% censorship attack after which the community coordinates an extra-protocol recovery fork to take out the attacker is legitimacy.16

And NFTs are a great example of how legitimacy works in practice as it determines which NFTs gather demand and value, and which do not.

Buterin, V. (2014). “A next-generation smart contract and decentralized application platform.” Retrieved from https://blockchainlab.com/pdf/Ethereum_white_paper-a_next_generation_smart_contract_and_decentralized_application_platform-vitalik-buterin.pdf

Tepper, F. (2017). “People have spent over $1M buying virtual cats on the Ethereum blockchain.” Retrieved from https://t.co/Ea718is6M5

Finzer, Devin. “The Non-Fungible Token Bible: Everything You Need to Know about NFTs.” OpenSea Blog, 11 Feb. 2021, https://opensea.io/blog/guides/non-fungible-tokens/

Finzer, Devin. “The Non-Fungible Token Bible: Everything You Need to Know about NFTs.” OpenSea Blog, 11 Feb. 2021, https://opensea.io/blog/guides/non-fungible-tokens/

Lopatto, Elizabeth. “The NBA on NFT.” The Verge, The Verge, 30 Mar. 2021, www.theverge.com/22348858/nba-nft-top-shot-dapper-labs.

Koonce, Lance, and Sean M. Sullivan. “What You Don't Know About NFTs Could Hurt You: Non-Fungible Tokens and the Truth About Digital Asset Ownership: Davis Wright Tremaine.” Insights Davis Wright Tremaine, www.dwt.com/insights/2021/03/what-are-non-fungible-tokens.

Gatto, James G. “NFTs And Intellectual Property: What IP Owners and NFT Creators Need to Know - Intellectual Property - United States.” Welcome to Mondaq, Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton, 29 Mar. 2021, www.mondaq.com/unitedstates/trademark/1051554/nfts-and-intellectual-property-what-ip-owners-and-nft-creators-need-to-know.

Koonce, Lance, and Sean M. Sullivan. “What You Don't Know About NFTs Could Hurt You: Non-Fungible Tokens and the Truth About Digital Asset Ownership: Davis Wright Tremaine.” Insights Davis Wright Tremaine, www.dwt.com/insights/2021/03/what-are-non-fungible-tokens.

Justin Cone. “The Skeptics' Introduction to Cryptoart and NFTs for Digital Artists and Designers.” Justin Cone, 1 Jan. 2021, justincone.com/posts/nft-skeptics-guide/

Ethereum. “Discussion for ERC-721 Royalties EIP. · Issue #2907 · Ethereum/EIPs.” GitHub, github.com/ethereum/EIPs/issues/2907.

Lopatto, Elizabeth. “The NBA on NFT.” The Verge, The Verge, 30 Mar. 2021, www.theverge.com/22348858/nba-nft-top-shot-dapper-labs.

Koonce, Lance, and Sean M. Sullivan. “What You Don't Know About NFTs Could Hurt You: Non-Fungible Tokens and the Truth About Digital Asset Ownership: Davis Wright Tremaine.” Insights Davis Wright Tremaine, www.dwt.com/insights/2021/03/what-are-non-fungible-tokens.

Young, Martin. “Are 'Social Tokens' the next Big Thing?” Cointelegraph, 2 Oct. 2020, https://cointelegraph.com/news/are-social-tokens-the-next-big-thing.

“$WRITE RACE.” Mirror, dev.mirror.xyz/vZxxUIeGMQK9NNLcrT0eDYZ6wXhXVr6vTQzztj1DaEA

“The Fractionalization of NFTs Will Lead to Better Social Tokens.” Mirror, jammsession.mirror.xyz/-xYcfFRlhDdLDSUgRMTYJAaRJBs2VG4LP34DnOV84mI.

Buterin, Vitalik. “The Most Important Scarce Resource Is Legitimacy.” Vitalik Buterin's Website, 23 Mar. 2021, vitalik.ca/general/2021/03/23/legitimacy.html.